Outlining: you either love it or you hate it. If you hate it, and would rather write by the seat of your pants, you’re what we call a pantser. They say there are two kinds of writers: plotters and pantsers. But I think you can be a good mix of both.

A couple of weeks ago, I gave a presentation in my writing group about the difference between plotting and pantsing, with an emphasis on storyboarding. It was received well, so after a few requests, I have decided to put all the juicy information in a (long) blog post.

Both plotting and pantsing have their pros and cons. What are you–a plotter, a pantser, or both? I, personally, am a bit of both, though I lean heavily on the plotting side. I outline, think of all the story beats, write each scene on sticky notes, and then plot it on my board.

But usually, the plot changes as the story progresses, and by the third act, I have to completely re-plot the remainder of the story just to keep my head on straight. By then, the outcome of the story has transformed into something I hadn’t expected when first plotting it out. And you know what? This is a good thing! Even the most ardent planners can be surprised with the direction their stories take.

What my process for plotting THE GIRL MADE OF GOLD looked like when I first started.

I mentioned that there are pros and cons to both pantsing and plotting, so let’s start there. Some of the pros of pantsing are:

- It lets your creative side take over

- As author Jessica Pennington said in a writing panel at Denver Comic Con last month, “It becomes less about me and more about the characters.”

Some of the cons, however, are:

- It doesn’t work well with deadlines

- You may run into the all-mighty Writer’s Block more frequently (I have a writer friend who is currently in this situation)

Or, as Chuck Sambuchino said (on pantsing), “Writing a book this way gives plotters hives.” I think that even the most creative, brilliant pantsers have something to gain from plotting. And that’s why for the majority of this post, I want to focus on plotting. Some of the types of plotting are:

- Writing general outlines

- Writing the different story beats, or events

- Daily diagrams: diagram the scene you’re going to work on each day (some people do this, plotting out the scene they’re about to write, and do it on a daily basis, rather than plotting the entire novel at once, before writing a single word)

- Book Bibles: notebooks with backgrounds on every character, details of the town in which your story takes place, etc.

- Some use the Fantasy Fiction Formula (by Deborah Chester), and use what’s called the SPOOC (structure, protagonist, objective, opponent, climax) method. If you’re unfamiliar with it, look it up. Many writers find it very useful.

- Storyboarding

All methods are effective and we are all so different, and work in such different ways, that what works well for some might not work well for others. Some writers even use a mix of all of them.

So, storyboarding. Why storyboard? Because…

- It allows feedback and input from others, including your agent and/or publisher

- It also prevents dead endings and stuck middles

- Helps us view the story as scenic rather than expository (the whole showing vs. telling thing)

- Helps us find the arc of the story

- It’s right-brained and creative (it is a visual representation of the story but also allows us to view the logical progression)

- It helps us remove scenes that don’t advance the plot

- It helps us find the right pacing and rhythm

- It allows us to write faster

I can attest to the writing faster part. Back in 2014, it took me about a month or two to plot out every single inch of HEMLOCK VEILS, so that when the time came to write, from start to finish, it took me only three months to write the entire 117,000-word manuscript.

“Storyboarding can greatly increase the ease and speed of writing a book,” Chuck Sambuchino says. “A journey can be a lot smoother if you know where you’re going… The magic of a storyboard is turning a book idea into a visual tool, which makes the story’s structure much easier to grasp and handle.”

While there are different methods of plotting, there are also different types of storyboarding (linear storyboarding, “W” storyboarding, etc.). And there are different methods to storyboarding (drawing it out on a white board, drawing on paper, using sticky notes or notecards, using software like Dramatica Pro, etc.). But the one I want to focus on in this post is the “W” Storyboard method.

First of all, if the idea of structure and outlining makes you fall asleep, remember you can keep it fun and engaging! Color code with markers, colored pencils, or even different sticky notes, and be as detailed as you’d like. You can even use pictures. Remember this is YOUR project–do what will motive YOU.

The “W” Storyboard Structure

There have been many variations of this over time, but the general points are the same, with a three-act structure (beginning, middle, and end). You can use it for any genre, whether you write fiction, non-fiction, memoirs, etc.

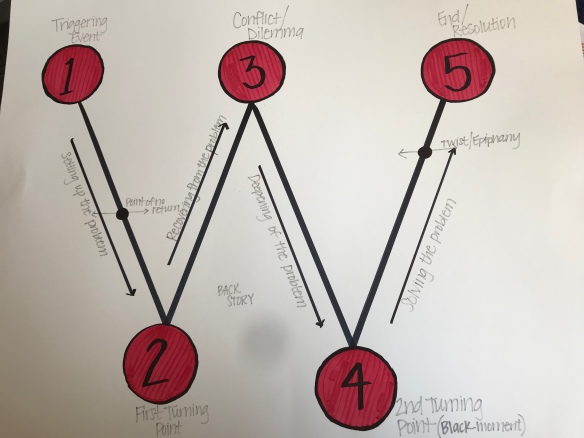

My favorite W storyboarding structure (sorry it it’s hard to read).

You can draw imaginary lines through your W and divide it up into three acts.

Act 1 (25% establish)

- Point 1: Triggering Event (the most important place to start your story)

- Down arrow: Setting Up the Problem (increasing the tension or drama)

- Point 2: First Turning Point (the first low point, where things bottom out)

Act 2 (50% build)

- Up arrow: Recovering from the Problem (where hope or new ideas provide positive momentum)

- Point 3: Conflict/Dilemma, or the Second Triggering Event (the “pop” moment, where your story percolates and then explodes)

- Down arrow: Deepening of the Problem

- Point 4: Second Turning Point, or the “Black Moment” (the lowest point in the book, hence point 4 being lower than point 2 on the W picture above)

Act 3 (25% resolve)

- Up arrow: Solving the Problem (it builds toward the resolution; new light or understanding has developed, and it brings a sense of completion or change)

- Twist/Epiphany, or the “OMG Moment” (complications arise on the way to the resolution)

- Point 5: End/Resolution (positive momentum builds)

There are different ways you can get started. Author Mary Carroll Moore brainstorms a list of 25 topics, chooses the 5 key points, and then places the points on the W.

Tips and Thoughts

- As Mary Carroll Moore says, you’re placing islands. But those islands must become continents, and storyboards provide that needed structure.

- One thing that is easy to keep in mind is that all your positive events in the story are always on the upslope and the negative events are always on the downslope. This is a great formula for where to place things.

- The W doesn’t have to be perfect! It can be all over the place, forming little squiggles or W’s within the larger W. As long as all five points of the W are met, it doesn’t matter how many ups and downs there are in between.

- Ensure it always reflects up and down momentum.

- Act 1 must always be on the downslope.

- Act 2 is partly up and partly down.

- Act 3 is always on the upslope.

- Right-brain thinkers are random-oriented and might enjoy the randomness of islands, so this helps them with structure.

- Always consider theme, voice, and pacing–they should be reflected on your storyboard.

- In your final edits, make sure the inner and outer story and dilemma are there.

- If your storyboard ever blocks your writing, go back to your brainstormed list of topics.

- Don’t worry if you don’t have it all figured out at first. Just fill in what you know, and then fill in the rest as you go.

- Your storyboard should change and grow; a static storyboard will not serve your book. Like I mentioned before, new things come up, new characters might be introduced, etc., and you want to be able to accommodate. Storyboards are great for organization, so add new ideas as they come to you!

- Do. Not. Be. Afraid. Of. It! It might seem overwhelming, but you will probably find it to be more of a friend than a foe.

How do other authors plot their books? Some examples of what other people do (just to show you how different we all are), are:

- Betsy Dornbusch writes her tagline first, then the back cover blurb, then a whole synopsis.

- Travis Heerman uses Scrivener for plotting and composition, but then uses MS Word for editing.

- Mary Carroll Moore uses three different “W” storyboards–one before the first draft, one during revisions, and one during the final edit.

- Hilary Mantel has a 7-foot tall bulletin board filled with bits of dialogue, plot ideas, and descriptions, and once she’s found a way to use the pieces, she removes them from her board.

- Kazuo Ishiguro spends two whole years researching and then one whole year writing the book. He has giant binders with flow charts, including not only plots, but character sketches and memories. I would call these binders Book Bibles.

Lestat from Interview with the Vampire may have been talking about being a vampire when he said, “The dark gift is different for each of us,” but I like to think he was talking about us writers. That’s the gist of this here. If you take anything away from this, let it be the reminder that we all have our own methods to our madness. I just hope that I (with help from resources by other great authors) was able to shed light on some helpful tips.

So, what is your process?

Like you, I’m a bit of both, though mainly a plotter. I love the “W” diagram and the idea of story boarding. Actually, I am doing a story board series after finishing my novel, which I am going to post on my blog page. I will be doing one story board per act, after I finish the initial round of blog posts that introduce the theme of my novel. I really got a lot out of this post – I will save it for Novel Number 2!

LikeLike